An Overview of the Healthy Parks Healthy People Movement

Chúk Odenigbo

“I felt my lungs inflate with the onrush of scenery—air, mountains, trees, people. I thought, ‘This is what it is to be happy.’” ― Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

Author and biologist Rachel Carson released her famous book, Silent Spring, in September 1962 (Lytle, 2007). Credited with starting and providing support to the environmental movement in North America, this book had far reaching impacts on overarching societal cultures, as well as government and private policies, in relation to the environment and nature (Vanderburgh, 2012). Traversing geographic frontiers, hitting a niche dominance in the proverbial ‘west,’ this book remained relevant throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, sparking research into how the environment impacts human health (Vanderburgh, 2012).

Taking up the mantle to push this further, Parks Victoria (Victoria, Australia), in collaboration with Deakin University, took the initiative to compile all of the existing research that linked nature to human health (Union International pour la Conservation de la Nature, 2010). In doing so, they officially initiated Healthy Parks Healthy People (HPHP) – a worldwide movement that seeks to use nature as a health resource in recognizing the “fundamental connections between human health and environmental health” (Parks Victoria, 2017; page 2). Although the movement has ‘parks’ in its name, this domain looks at the collectivity of nature, ranging from parks to forests to oceans to gardens, in its goal of providing resources in the interest of public and community health (Townsend, Henderson-Wilson, Warner, & Weiss, 2015). Providing an alternative to the WHO focus on the quality of the physical environment, HPHP considers environmental deprivation and the human condition (Townsend et al., 2015). In other words, the WHO concentrates on how the physical environment (e.g., air quality) affects human health whereas HPHP focuses on the impact of being disconnected from nature and what it means to be a healthy human.

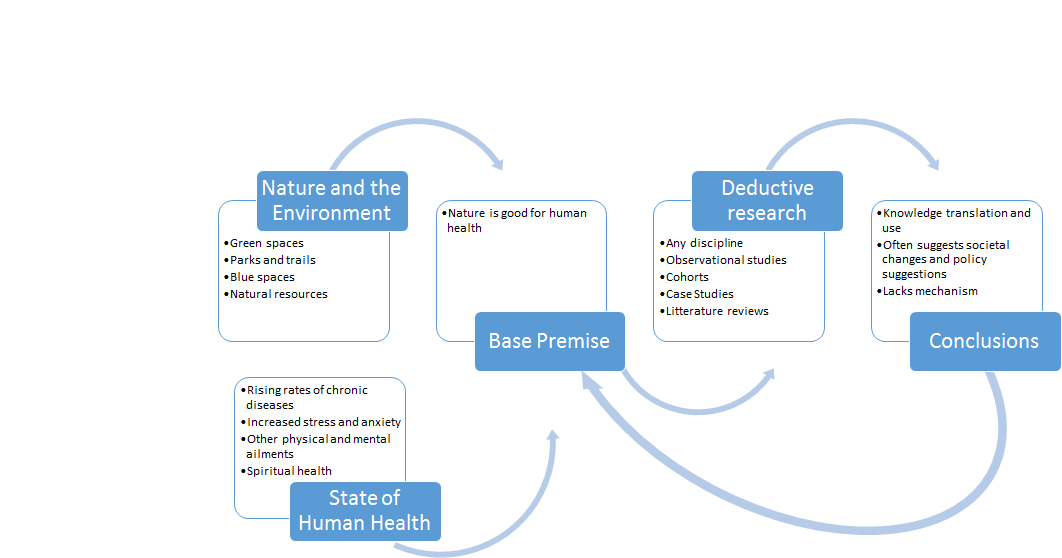

Figure 1: Research process using the HPHP approach to health.

As shown in Figure 1, the HPHP movement starts and ends with the premise that nature is good, and even essential, for human health. This can be approached from many varying bodies of work including the psychological arts and sciences, economics, conservation sciences, recreation and leisure, public health, and religion and spirituality (Maller et al., 2008). Research following a HPHP framework can be qualitative, quantitative or use mixed methods; however, thus far, it has consistently involved a group of people being observed, surveyed, interviewed, evaluated and/or discussed. Research in this field is approached deductively, meaning that its goal is to develop and test a hypothesis, and then contextualise the new knowledge in a way that can improve human health.

One of the key weaknesses of HPHP is that the mechanisms leading to health outcomes are rarely explored. In essence, a correlation is seen between A and B, but the way in which A leads to B is rarely touched upon. HPHP remains, nonetheless, a unique perspective that ties in many disciplines and fields of study into one movement.

Unlike fields such as development studies or conservation sciences, there is no pressure on the researcher for their findings to be immediately applicable in a real-world context when using the HPHP framework. The accumulation of information, facts and theories contributes to the growing body of literature and will ultimately serve to influence and inspire policy and practice. Many countries have started crafting policies based on the HPHP movement or modifying government structure to properly incorporate the voice of HPHP in their parks and public health outreach programs. Some notable mentions include Scottish National Heritage, who have launched a campaign promoting time in nature to support wellbeing (Macpherson, 2017), and the Korean National Park Service who provide free entry to parks for those carrying doctor’s prescriptions (Oh, Won, & Myeong, 2016). In Canada, HPHP efforts are still very much in infancy. As more studies on health and nature are brought forth using the HPHP framework, it will be interesting to see how HPHP develops and morphs both academically and practically, to adapt to the dynamic field of public health.

References

- Lytle, M. H. (2007). The Gentle Subversive: Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, and the Rise of the Environmental Movement. Oxford University Press.

- Macpherson, A. (2017). “Our Natural Health Service”. Scottish National Heritage. https://www.nature.scot/professional-advice/contributing-healthier-scotland/our-natural-health-service

- Maller, C., Townsend, M., St Leger, L., Henderson-Wilson, C., Pryor, A., Prosser, L., & Moore, M. (2008). “Healthy Parks Healthy People: The health benefits of contact with nature in a park context.” Parks Victoria. https://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/310750/HPHP-2nd-Edition.pdf.

- Oh, J. G., Won, H. J., & Myeong, H.-H. (2016). A Study on the Method of Ecosystem Health Assessment in National Parks. Korean Journal of Ecology and Environment, 49(2), 147‑152. https://doi.org/10.11614/KSL.2016.49.2.147

- Parks Victoria. (2017). “A Guide to Healthy Parks Healthy People”. Victoria State Government. http://www.hphpcentral.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Parks-Victoria-HPHP-Guide-2017-Interactive-Final_hi-res.pdf

- Townsend, M., Henderson-Wilson, C., Warner, E., & Weiss, L. (2015). “Healthy Parks Healthy People: The State of the Evidence 2015.” Parks Victoria. https://parkweb.vic.gov.au/about-us/healthy-parks-healthy-people/the-research.

- Union International pour la Conservation de la Nature. (2010). “Des Aires Protégées Pour Des Populations En Meilleure Santé.” UICN. https://www.iucn.org/fr/content/des-aires-prot%C3%A9g%C3%A9es-pour-des-populations-en-meilleure-sant%C3%A9.

- Vanderburgh, W. L. (2012). “Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring.” In The Origins of Modern Environmental Thought, 15:28–42. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.