A Public Health Approach to Population Mental Wellness

In 1942, the Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA) approved its first resolution concerning mental health. That resolution called for improvement to the provision of mental health services for Canadians in light of the effect of the war effort on the availability of such services domestically. Between 1942 and 2003, mental health and mental wellness had been, directly or indirectly, the subject of five additional resolutions and a discussion paper. Appendix 1 provides a summary of these initiatives. “Mental health” was subsequently identified as a subject for development during CPHA’s Policy Forum at Public Health 2013.

Population Mental Wellness (PMW) has been an underlying theme in much of the Association’s recent work, whether it be to address children’s access to play, substance use, the social determinants of health, stigma and racism, Jordan’s Principle or sexual health. As such, the Association recognizes the innate intersection among health promotion, public health and population mental health and wellness so that every person possesses the capacity “…to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It [mental wellness] is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity.”1

Significant strides have been and continue to be taken provincially/territorially, nationally and internationally to attain this goal from population mental health/wellness, mental health and mental illness perspectives. The challenges, however, are to distinguish between population mental health and wellness, and mental health and mental illness, and to understand how personal, social and ecological determinants of health can affect PMW, and how public health approaches can be applied.

RECOMMENDATIONS

CPHA calls on the federal government to work with provinces, territories, municipalities, communities, Indigenous Peoples communities and governments, and industries to take action in the following areas:

National Strategy

- Continue developing a national strategy for population mental wellness that incorporates personal, social and ecological determinants of health and addresses the effects of racism, colonialism and social exclusion on mental health and wellness, using a life-course approach;

- Support this national strategy by describing an approach to implementation and providing adequate funding to address current needs through mental wellness accords with the provinces, territories and Indigenous governments, and support initiatives at the community level;

- Monitor progress on the implementation of the national strategy through agreed-to performance measures that build on current performance measurement activities.2

Policy and Programs

- Develop and implement a health/mental-health-in-all-policies approach to policy and program development;

- Establish a life-course, culturally sensitive approach when developing mental wellness programs, with special emphasis on:

- Perinatal, postpartum, infant, child and youth programming;

- Seniors;

- Gender;

- LGBTQ2S+ communities;

- Black and racialized communities;*

- Refugees;

- The homeless;

- Indigenous Peoples; and

- Peoples with disabilities, including those with chronic health conditions;

- Develop adaptable approaches for addressing mental health that are appropriate to diverse situations;

- Make programs universal in nature but proportionate to meet the requirements of those who have the greatest need;

- Provide universally available, affordable, high-quality, developmentally-appropriate early childhood education and care [that is culturally sensitive];

- Develop poverty reduction programs that meet the needs of those who need them most;

- Continue efforts to address the needs of Indigenous Peoples by acting on the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and supporting strength-based approaches to mental wellness that include Indigenous mental wellness models;

- Support the development of provincial, territorial and regional/community PMW planning and performance measurement activities;

- Recognize and develop approaches to address anxiety and grief resulting from climate change, COVID-19 and the opioid poisonings crisis;

- Continue efforts to support and enhance workplace mental health programs.

* Throughout this paper efforts have been made to use non-stigmatizing language that reflects current practice. This language may change over time as social and cultural practices change. As such, the language used in this statement may appear dated depending on current practice.

Emergency Response

- Develop and implement programs and processes to address PMW concerns arising during emergency responses;

- Develop and support population recovery interventions following an event.

Research, Surveillance and Evaluation

- Support surveillance and research concerning the determinants of population mental wellness and develop approaches for addressing any shortcomings; and

- Develop and implement monitoring and evaluation methodologies for all programs.

Definitions

- Mental Health – the state of your psychological and emotional well-being. It is a necessary resource for living a healthy life and a main factor in overall health (PHAC)

- Mental Illness – alterations in thinking, mood or behaviour associated with significant distress and impaired functioning (PHAC)

- Mental Wellness – a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community (WHO)

- Mental Health Promotion – programs that lead and support activities which promote positive mental health (PHAC)

- Population Mental Health – the state of psychological and emotional well-being at the population level and among different groups of people

- Population Mental Wellness – an overall state of well-being where people in different populations can realize their own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and be able to make a contribution to their community

Nomenclature

The current literature concerning this subject predominantly uses the term mental health while other terms such as mental wellness and population mental health are also used from time to time. For this discussion, the term population mental wellness (PMW) has been proposed to describe the intersection between mental health and public health and those activities that are based on public health practice and aimed at population mental health. The term is used in this document unless the material being discussed directly uses another term.

Metrics and Data

Throughout the paper, effort has been made to incorporate data from metrics developed to measure aspects of population mental health (wellness). There is a limited amount of such data available. As a result, on occasion, data from personal mental health metrics (e.g., suicide and stress) have been used as proxies for population-based concerns.

Acknowledgements

An iterative process was used to develop this position statement that involved the efforts of volunteers, practicum students and review by external partners, each of whom have provided components of the work. The Association thanks them for their efforts to support the completion of this position statement.

Health Equity Impact Assessment

In accordance with current administrative policy, a Health Equity Impact Assessment was conducted on this position statement prior to final approval by CPHA’s Board using the methodology that was approved in December 2019. The assessment was conducted by a group of four volunteers from within CPHA’s membership who had not participated in the development of the statement. The Association thanks these members for their work.

CONTEXT

The Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO)3 defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” and recognizes that health is a basic human right. It also recognizes among other things that an integration of social, ecological and personal factors is required so that each person can cultivate resiliency in the face of stress, setbacks and adversity, and achieve their best result. Some 40 years after the ratification of WHO’s Constitution, the Honourable Jake Epp, then Minister of Health and Welfare Canada, released “Mental Health for Canadians: Striking a Balance”4 which provided greater clarity for the Canadian context by defining “mental health” as:

“the capacity of the individual, the group and the environment to interact with one another in ways that promote subjective wellbeing, the optimal development and use of mental abilities (cognitive, affective and relational) and the achievement of individual and collective goals consistent with justice and the attainment and preservation of conditions of fundamental equality.”

That paper further described a series of guiding principles and presented a discussion of the challenges to achieving “mental health.” The requirement for a strategy to address mental health promotion and illness prevention was described in a 2006 Senate report,5 while the first mental health strategy for Canada was released in 2012.6 The federal budget of 2017 subsequently provided funding over a 10-year period to address, in part, the provision of access to mental health and substance use disorder (addiction) services in provinces and territories.7

Recently, the WHO affirmed that “there [is] no health without mental health,” and that the focus of national mental health policies should both address the mental disorders that exist within the country and promote the mental health of the population.8 It is recognized that a range of socioeconomic, biological and environmental factors affect mental health and that population-level mental health (and wellness) can be promoted, protected and restored through cost-effective public health and inter-sectoral strategies and interventions.

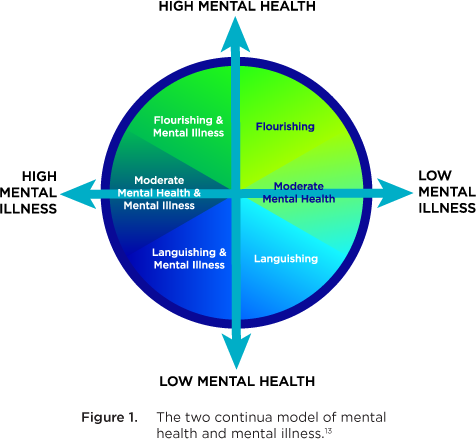

DEFINING MENTAL HEALTH AND MENTAL ILLNESS

Mental health is “the state of your psychological and emotional well-being. It is a necessary resource for living a healthy life and a main factor in overall health.”9 Mental illness, however, is “… characterized by alterations in thinking, mood or behaviour associated with significant distress and impaired functioning. Examples of specific mental illnesses include mood disorders such as major depression and bipolar disorder; schizophrenia; anxiety disorders; personality disorders; eating disorders; problem gambling; and substance dependency.”10 While mental health and mental illness are distinct concerns, they are inter-related, as described in the two continua model (Figure 1).11,12

The two continua model shows that it is possible to have flourishing mental health in parallel with a mental illness or have languishing mental health but be free from mental illness. This relationship is further complicated as the presence of flourishing mental health may mitigate some aspects of mental illness.14 In addition, the concept of “recovery” adds to this relationship as it “refers to living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life, even when a person may be experiencing ongoing symptoms of a mental health problem or illness. Recovery journeys build on individual, family, cultural, and community strengths and can be supported by many types of services, supports, and treatments.”15

Underlying this two continua relationship is the influence that the social determinants,16 the environment,17 and personal relationships (including intimate partner violence)18,19 and their intersectionality have on mental health. This inter-relationship also speaks to the utility of a social ecological model* to better define these relationships,20 and the use of the term population mental wellness to describe the influence that population-level interventions can have on both the perception of mental health and the mitigation of mental illness. Such models have been developed to explain the inter-relationships that mediate, for example, child development,21 violence,22 and suicide.23

* A Social Ecological Model studies how behaviours form based on characteristics of individuals, communities, nations and the levels in between. In the 1970s, Urie Bronfenbrenner developed the model as an Ecological Framework for Human Development, and it has since been used to address public health problems as a means of bridging the gap between personal behavioural considerations that focus on small settings, and community or systems-based considerations.

THE CANADIAN SITUATION

Perceived Mental Wellness

In Canada, frameworks for and indicators of population mental health and wellness have been developed by the Mental Health Commission of Canada6,24 and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).25,26 The PHAC framework also presents ways to measure positive mental health outcomes, individual determinants, community determinants and societal determinants.27 Components of these frameworks have been used to assess the perceived mental wellness of Canadians. Specifically, the PHAC framework and indicators have been supported with information concerning self-rated mental health and mental wellness, including happiness, life satisfaction, psychological well-being and social well-being. This information is presented in a portal concerning the mental health of people living in Canada.28

The information presented in the current paper is based on the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS),† which provides, as part of its analysis, a summary of Canadians’ views concerning their mental health that informs the PHAC framework (noting, however, that it does not include information concerning First Nations adults and youth living on-reserve). During the period 2017/2018, approximately 61% of Canadians viewed their overall health as either very good or excellent. Over that same period, the proportion of Canadians who viewed their mental health as either very good or excellent was 69%. This level is lower than for the period 2015/2016 (72%). Alternatively, 7% of CCHS respondents thought their mental health was either poor or very poor in 2017/2018, which was up from 2015/2016 (5.4%). During 2017/2018, a higher proportion of men (71.9%) rated their mental health as excellent or very good compared with women (67%). Excellent or very good perceived mental health was highest in the 12 to 17-year-old age group at 75%, followed by those aged 65 years or older (72%), then 35 to 49 year-olds and 50 to 64 year-olds, at 69% and 66% respectively. Those aged 18 to 34 years had the lowest proportion (66.3%) of very good or excellent self-perceived mental health. First Nations People living off-reserve self-reported their mental health as low 1.9 times more often than non-Indigenous people, while Métis self-reported poor mental health 1.5 times more often.29

† The CCHS is a cross-sectional survey that collects information related to health status, health care use and health determinants for the Canadian population. It is designed to provide reliable estimates at the health region level every two years.

Information concerning the self-reported perceptions of health, including mental health, for First Nations People living on-reserve can be found in the First Nations Regional Health Survey (FNRHS).30 First Nations adults self-reported their mental health as excellent or very good 50.5% of the time and poor 13% of the time, while youth reported very good to excellent mental health 55.5% of the time and poor mental health 11.6% of the time. For youth 12 to 14 years of age, 62.1% reported excellent to very good mental health, while those 15 to 17 years of age reported this level 49.9% of the time, and those 18 to 29 years of age reported this level 50.9% of the time.

The CCHS and the FNRHS both collect other self-reported mental health and wellness information that are reflective of the current state of mental health among those living in Canada. Among the measures found in the CCHS, the sense of community belonging is telling. The results from the 2017/2018 survey show that the greatest sense of community belonging existed in the 12 to 17 year-old population and dropped to its lowest among 18 to 34 year-olds. It then increased with each subsequent age group.

In addition, during 2017/2018, the CCHS showed that more than 6.6 million Canadians (about 21% of the population) reported high levels of stress, with the rates being highest among 35 to 49 year-olds followed by 18 to 34 year-olds and 50 to 64 year-olds. Adults over the age of 65 reported the lowest stress levels. Women generally reported higher levels than men for each age group. The FNRHS results showed that on-reserve First Nations adults reported daily stress that was “quite a bit/extremely stressful” 12.9% of the time and “not at all stressful” 16.2% of the time, while youth reported “quite a bit/extremely stressful” 15.9% of the time and “not at all stressful” 20.2% of the time.

Other factors that were shown by the CCHS data to influence population mental wellness ratings as either very good or excellent included:

- the province in which a person lives (residents of Newfoundland and Labrador have the highest perception of psychological well-being, while Manitobans have the lowest);

- whether a person lives in the country or in the city (rural dwellers reported higher levels of satisfaction than urban dwellers); and

- income, where those in the top 20% of income self-reported as having better mental health than those in the lowest 20%.

An additional, albeit contrarian, indicator of population mental wellness may be the number of suicides in Canada. Each year about 4,000 people (on average 11 per day) die by suicide. The groups at greatest risk are:31,32

- Men and boys, for whom the rate is about three times that for women and girls;

- People serving federal prison sentences;

- Survivors of suicide loss and suicide attempt;

- People 45-59 years of age, among which age group one third of deaths by suicide occur;

- Youth and young adults (15-34 years of age), for whom suicide is the second leading cause of death; and

- Persons in all Inuit regions.

Thoughts of suicide and suicide-related behaviours are more frequent among LGBTQ2S+ youth in comparison with their non-LGBTQ2S+ peers. This refers to those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, Two-Spirit or queer/questioning youth.28

Of particular concern is the rate of suicide among First Nations People living on-reserve. The FNRHS data shows that 16.1% of adults and 16% of youth had lifetime suicide ideation, while 11.3% of adults and 10.3% of youth had lifetime suicide attempts. Lifetime suicide attempts were reported in 7.1% of youth 12 to 14 years of age, in 13% of youth aged 15 to 17, in 12.7% of young adults 18 to 29, in 12.4% of adults 30 to 49 and in 8.3% of adults over 50.

Two other populations should receive additional consideration. A 2016 report estimated that 235,000 people living in Canada experienced homelessness, with 30-35% of those people suffering from mental illness, and 20-25% experiencing concurrent disorders (mental illness and substance use disorder), while up to 75% of women experiencing homelessness have mental illnesses.33

In addition, it has been reported that refugees to Canada have increased rates of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, and being a refugee is a risk factor for psychosis. Similarly, refugee children have increased rates of mental health problems.34 A targeted, trauma-informed, culturally sensitive approach could help address the unique challenges in achieving population mental wellness for both these groups.

Economic Effect

In 2015, approximately 13.9% of Canadians over the age of 12 years sought the assistance of a health professional concerning their mental well-being, with the highest rates among those aged 18-34 and 35-49. In addition, about 21.4% of the working population experienced mental health problems and illnesses that could affect productivity.35 Women were more likely to seek support than men. Approximately one third of hospital stays in Canada were due to mental disorders,36 and about 500,000 Canadians weekly were unable to work due to mental health problems.37 Within these statistics, it is difficult to separate the effect of languishing mental health/wellness from that of mental illness; however, the economic burden of all mental illness was estimated at $51 billion per year in 2011,38 which represented 2.8% of Canada’s gross domestic product in that year.39

Conversely, improved treatment of depression among employed Canadians could potentially boost Canada’s economy by up to $32.3 billion a year, while improved treatment of anxiety could boost the economy by up to $17.3 billion a year.40 More recently, the potential return on investment (ROI) associated with mental health promotion and mental illness prevention activities has been estimated at $7 in reduced health care costs and $30 in reduced losses of productivity and social costs for each $1 invested.41 A separate study from Great Britain, as cited by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), assessed the ROI of different interventions.42 Each type of intervention produced a different ROI; however, those that appear to have the best economic value included:

- Parenting and early years programs (ROI of 14.3);

- Life-long learning programs (including mental wellness support in schools and continuing education) (ROI of 83.7);

- Workplace interventions (ROI of 9.69);

- Positive mental health programs (lifestyle and social support programs) (ROI of 7.9); and

- Community interventions from environmental improvements to bridge safety (ROI of 10).

This report also noted that a health-in-all-policies* approach might be effective for achieving the greatest improvement for population mental wellness and illness prevention. Similarly, a “mental-health-in-all-policies” approach has been investigated by the European Union.43

* Health-in-all-policies is “an approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the health implications of decisions, seeks synergies, and avoids harmful health impacts in order to improve population health and health equity. It includes an emphasis on the consequences of public policies on health systems, determinants of health and well-being.” (World Health Organization, 2014. Health in All Policies. Helsinki Statement Framework for Action. World Health Organization.)

A report from Canada has identified the need for public health strategies to improve the mental wellness of Canadian children. It placed emphasis on the benefits of early child development but also noted its potentially limited effect on mental health and the limited funding available for such programs.44

In spite of these potential economic benefits, only about 7.2% of Canada’s health care budget is dedicated to mental health, with the bulk of that funding seemingly directed to treatment programs rather than prevention and promotion. The latter point is difficult to verify as family physicians provide about two thirds of the mental health care services for people living in Canada.45 In addition, substance use disorder counsellors, psychologists, social workers and specialized peer support workers provide the bulk of mental health and mental illness services, but these services have only limited support through the health care system. For example, psychologists are often paid through private insurance while publicly-funded mental health services suffer from long wait lists for access. As such, those without access to private insurance or of lower socio-economic status may have difficulty accessing services. Consequently, Canadians are estimated to spend almost one billion dollars ($950 million) on counselling services each year with 30% of it being out of pocket.46

A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH TO POPULATION MENTAL WELLNESS

Canadian Perspective

Public health is an approach to maintaining and improving the health of populations that is based on the principles of social justice, attention to human rights and equity, evidence-informed policy and practice, and responding to the underlying determinants of health. Such an approach places health promotion, health protection, population health surveillance, and the prevention of death, disease, injury and disability as the central tenets of all related initiatives. Such an approach has a long history of success for preventing illness and promoting health,47 and is being used to improve population mental health and wellness with the potential to reduce mental illness treatment costs.48

The foundations of public health are the social and ecological determinants of health, social justice and health equity. Underscoring these foundational elements is the social gradient whereby people who are from a less advantaged socioeconomic position have worse health (and shorter lives) than those who are more advantaged.49 Influences on one’s position on this gradient include gender, gender identity, race, age, ableism, and social status. In Canada, this gradient is evident for suicide mortality, self-rated mental health, and mental illness hospitalizations, while low standard housing or homelessness, household food insecurity and income insecurity are structural drivers that result in poor mental wellness. Other areas that have a strong social gradient include smoking and high alcohol consumption. Of greatest concern among these drivers is their influence on early childhood development where the level of vulnerability at the lower end of the social gradient is almost double that at the higher end. An important structure for building resilience and promoting positive mental health of children is the provision of universally affordable, high quality, developmentally appropriate early childhood education and care.

The 2018 report of PHAC and the Pan Canadian Public Health Network50 further indicated that the following approaches might mitigate these challenges:

- Adopt a human rights-based approach to action on the social determinants of health and health equity;

- Intervene across the life course with evidence-informed policies and culturally safe health and social services;

- Intervene on both the downstream and upstream determinants of health and health equity;

- Deploy a combination of targeted interventions, and universal policies and interventions;

- Address the sociocultural processes of power, privilege and exclusion and the living, working and environmental conditions that they influence;

- Implement a “health/mental-health-in-all-policies” approach; and

- Carry out ongoing monitoring and evaluation.

CPHA has developed position statements that include consideration of the mental wellness implications of early childhood education and care,51 racism and public health,52 children’s access to unstructured play,53 and Jordan’s Principle,54 while the Canadian Coalition for Public Health in the 21st Century has issued statements on housing security55 and basic income.56 The recommendations contained in these statements align with the recommendations noted above.

Indigenous Peoples

Of particular concern is the mental wellness of Indigenous Peoples, where the results of racism, colonization, cultural genocide and structural violence include dislocation of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples from their land, culture, spirituality, languages, traditional economies and governance systems, resulting in the erosion of family and social structures. In particular, residential and day schools resulted in, among other things, physical, psychological, emotional and sexual abuse of certain children. These events have resulted in inter-generational trauma, and increased susceptibility to future illness. It also leaves some survivors unprepared to become parents themselves, affecting parenting capabilities and family dynamics, and resulting in some persons continuing to live with substance use disorder, and the effects of physical and sexual abuse. Similarly, the ongoing implementation of the Indian Act and the enforcement of the reserve system have exacerbated these effects for First Nations Peoples. A description of the effect of this racism on Indigenous Peoples in Canada is presented in the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission57 and the associated Calls to Action.58 The effect of these inequities on the current generation of Indigenous children can be seen, in part, with the ongoing efforts to address Jordan’s Principle.52

Steps are being taken by Indigenous organizations, and federal, provincial and territorial governments to improve Indigenous Peoples’ mental wellness. The First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum describes a First Nations viewpoint and methodologies using a strength-based approach to improving their mental wellness,59 while the Inuit have prepared an action plan to respond to their mental wellness needs.60 Appendix 2 contains a list of the provincial and territorial action plans supporting Indigenous Peoples’ mental wellness.

An International Perspective

Considerations similar to those identified in Canadian reports have also been recognized internationally.61 Both the lower and middle portions of the social gradient are recognized as being disproportionately affected by poor mental well-being (health), and the importance of taking actions to improve the conditions of everyday life are noted (reducing income, housing and food insecurity, for example). Actions to improve mental wellness were noted as being required throughout the life course, with special consideration being given to early childhood development (including perinatal and post-partum supports) as giving children the best start in life will result in the greatest economic, societal and mental health benefits.62 Actions to address these concerns should support the entire population, but proportionately to the need, as a means of reducing the social gradient, and they should address concerns at the community, country and systems levels. Recent investigations have also shown a link between population well-being and economic growth.63 The underlying structure of a wellness-based economy should:

- Support upward mobility and improve lives;

- Translate social improvement to well-being outcomes for all segments of the population;

- Reduce inequalities; and

- Foster environmental and social sustainability.

These outcomes were shown to be achievable through: education and skills development; provision of physical and mental health care; social protection and supports; redistribution to support socio-economic resilience; inclusive communities; and gender equality.

Determinants of Mental Well-being

Community-based interventions are influenced by the environment at each of the levels of the social ecological model, so that, to be effective, interventions are required in the personal, social and environmental spheres.64 Similarly, the effectiveness of community-based interventions at the individual level may vary based on individual genetics, behavioural patterns and personal factors. As a result, it is important to improve population mental wellness while maintaining a community’s ability to address individuals’ mental health concerns.65 Underlying these considerations is the effect that personal, social and environmental conditions have on gene expression. These epigenetic effects are most obvious in children and youth, and these age groups should receive the greatest attention.66,67

In addition to the previously noted influences, systemic changes to the environment (climate change, resource extraction, crisis situations, etc.) influence mental wellness.68 One ongoing concern is the effect of climate change,69 where grief associated with the anticipated loss of our current environment and anxiety related to future changes to the ecosystem are evident.70,71 Similarly, changes to the ecosystem resulting from resource development affect population mental wellness through the disruption of local environmental and social determinants. This effect is most evident in the North with the loss of traditional cultural activities, disruption of land-based activities, and changes in animal migratory patterns that affect hunting and food security.72 These changes also affect the quality and longevity of the winter road system thereby reducing access to food and consumer goods. Damage to local ecosystems, and the loss of traditional cultures and norms result in the loss of identity, and languishing mental health and mental illness, while migratory human populations (i.e., temporary workers from outside the area) affect the existing local social structures and determinants of health.

Similarly, recent natural disasters, extreme weather events and infectious disease outbreaks have resulted in stress, grief and anxiety. One study has suggested that people affected by psychological trauma during natural disasters outweigh those with physical injury by 40:1.73 In addition, a 2014 study showed that less than half (45%) of individuals who experience emotional or psychological trauma as a result of a disaster recover within one year, while 23% had recovery times greater than one year.74

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a striking example of the influence of a crisis situation on the social determinants of health and their subsequent effect on vulnerable populations. While there have been many instances of strengthened community caring and support for those in need, there have also been harms resulting from the pandemic and the actions taken to suppress it. The United Nations published separate policy briefs* concerning the pandemic’s effect on women75 and children76 from an international perspective. The immediate effects on women include: economic loss; loss of access to health services; and increases in gender-based violence. The effects on children include: falling into poverty; exacerbation of the learning crisis; threats to child survival and health; and risks to child safety. Such harms have immediate effects on mental well-being.

* Links to other related policy briefs prepared by the United Nations system, including mental health, can be found online.

These results highlight the need to strengthen personal and community capacity to respond to public health crises through the development of individual and community resilience. Intrinsic to these developments is the capacity of individuals to adapt and respond to stressful situations; this capacity is learned most easily by children and youth but can be strengthened throughout the life course. Healthy adaptation is based on a strength-based framework that includes emotional self-regulation, strong interpersonal relationships (supportive families and friends), and the ability to understand and explain what someone is feeling,77 which support psychological endurance. The integration of these capacities by individuals provides communities the ability to respond to and recover from crisis situations. Core components of community resilience include: people; systems thinking; adaptability; transformability; sustainability; and courage.78 Resiliency characteristics that are more specific to Indigenous Peoples include spirituality, holism, resistance and forgiveness; while obstacles to overcome for resilience include the phenomenon of co-dependency, lack of trust, and refusal of authority.79 Underlying these characteristics are the concepts of cultural identity and, for community resilience, the capacity of community members and families to be resilient themselves.

† Individual resilience refers to those behaviours, thoughts and actions that promote personal well-being and mental health. People can develop the ability to withstand, adapt to, and recover from stress and adversity — and maintain or return to a state of mental well-being by using effective coping strategies.

‡ Community resilience is a measure of the sustained ability of a community to utilize available resources to respond to, withstand, and recover from adverse situations.

GOVERNANCE CONSIDERATIONS

The Constitution Act, 1867 assigned responsibility for the delivery of health care services in Canada to provincial (and now territorial) governments, although the federal government may assume a coordination and leadership role in support of activities of mutual interest.80 An additional factor affecting these relationships is the ongoing implementation of Indigenous self-government. A recent overview of the systems and approaches to mental wellness in Canada demonstrates the complexity of the current system.81 Within this framework, PHAC has compiled data, strategies and systematic reviews concerning mental health promotion.1 Included in this work are surveillance indicator frameworks for youth (aged 12 to 17)25 and adults (over 18 years of age)26 that support a conceptual framework for the surveillance of positive mental health in Canada.82

The National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy (NCCHPP) has developed summaries (to 2017) of provincial and territorial strategies in mental health,83 Indigenous-specific mental health and/or wellness strategies,84 and strategies related to suicide prevention.85 These summaries also include links to recent materials that discuss approaches to population mental health in Canada. Appendix 3 provides an update of the available provincial and territorial strategies.

LOOKING FORWARD

The intersection of population mental health and public health is established (although poorly resourced and implemented), while actions that are being taken at the community and systems levels are having positive effects at the personal level. The challenge is to translate this potential into consistent, effective and measurable actions by all levels of government to meet the needs of all living in Canada. The 2004 report of the WHO, Promoting Mental Health, noted that effective public health and social programming can achieve the promotion of mental health, and that the emphasis should focus on:

- Early childhood interventions;

- Social support for old age populations;

- Mental health promotion in schools and at work;

- Housing policies;

- Violence prevention;

- Community development programs; and

- Programs targeted at vulnerable groups.86

Recently, the Canadian Mental Health Association provided similar recommendations,87 including:

- Reviving and implementing a national-level mental health promotion strategy, including quality standards and adequate funding;

- A mental-health-in-all-policies approach;

- Support for research, economic analysis and program evaluation;

- Providing adequate funding for mental health promotion;

- Replicating, scaling and making sustainable population-based programs that are accessible, culturally safe, intersectional and address the social determinants of health;

- Investing in social-marketing initiatives that enhance mental health awareness and reduce stigma; and

- Increasing social spending to promote social inclusion and freedom from violence and discrimination and to improve access to economic opportunity.

Many of these recommendations fall within the roles and responsibilities of public health organizations that may or may not be appropriately funded to take on this work. In the Province of Ontario, for example, such steps have been taken with the implementation of a mental health promotion guideline.88 As such, progress is being made to address many of these concerns at the provincial, territorial and community/regional levels, but further work is needed to develop an evidence-informed national strategy that:

- Is applicable equitably at the provincial, territorial and community/regional levels;

- Is supported with adequate resources; and

- Provides clear performance indicators that support evaluation and adjustment.

Within the strategy, universal support is required for a life-course approach that places emphasis on perinatal, infant, child and youth programs that are proportional to the need of the child. Similar considerations are required to meet the needs of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

APPENDIX 1

Canadian Public Health Association Mental Health Resolutions

Resolutions that include mental health

1942 Mental Health. Limit overcrowding of existing facilities and support for new building as required.

1970 Housing. Promotion of suitably designed and equipped facilities for health, education, recreation and other social services for multi-family dwellings.

1983 Health for the Elderly. Raise public awareness and advocate on behalf of the elderly concerning the quality of life of the elderly population.

1993 User Charges and the Canada Health Act. Prohibit changes to or interpretation of the Canada Health Act that would compromise universality of health care by the adoption of user charges.

2003 Suicide Prevention. Support for the development of a Canadian Strategy for Suicide Prevention, and enhance the public’s knowledge of suicide as a public health issue.

Discussion paper that includes mental health

1996 Discussion Paper: The Health Impact of Unemployment. 14 p.

APPENDIX 2

Mental Wellness Actions Plans for Indigenous Populations

| Location | Name | Organization | Year | Progress | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | A Path Forward: BC First Nations and Aboriginal People's Mental Wellness and Substance Use Ten Year Plan | First Nations Health Authority | 2013 | ECS, EIT, FH, IB, SUR, YO | |

| AB | Alberta Aboriginal Mental Health Framework | Government of Alberta | 2009 | CB, CD | |

| AB | Honouring Life: Aboriginal Youth and Communities Empowerment Strategy (AYCES) | Government of Alberta, Alberta Health Services | 2009 | CB, EIT, YO, YW | |

| SK | First Nations Suicide Prevention Strategy | Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations' Mental Health Technical Working Group | 2018 | CD, SUR, YW | |

| MB | Manitoba First Nations Health & Wellness Strategy Action Plan: A 10 Year Plan For Action 2005 - 2015 | Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs | 2006 | CB, CD, IB | |

| YT | Yukon First Nations Wellness Framework | Council of Yukon First Nations | 2015 | IB | |

| NVT | Nunavut Suicide Prevention Strategy | Government of Nunavut; Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.; Embrace Life Council; Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 2010 | 2015 | CD, ECS, YO |

| NVT | Resiliency Within: An Action Plan for Suicide Prevention in Nunavut 2016-2017 | Government of Nunavut; Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.; Embrace Life Council; Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 2016 | EIT, YO, YW | |

| NVT | Inuusivut Anninaqtuq Action Plan 2017-2022 | Government of Nunavut; Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.; Royal Canadian Mounted Police V-Division; Embrace Life Council | 2017 | CD, ECS, IB, SUR, YO, YW | |

| Inuit Nunangat | Alianait Inuit Mental Wellness Action Plan | Alianait Inuit-specific Mental Wellness Task Group | 2007 | CB, CD, FH, IB, YO | |

| Inuit Nunangat | National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy | Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami | 2016 | 2018, 2019 | ECS, FH, IB, YW |

CB: Capacity Building

CD: Community Development

ECS: Early Childhood Programs & Services

EIT: Elder Inclusion & Teachings

FH: Family Health & Wellness

IB: Identity Building

SUR: Substance Use Reduction

YO: Youth Opportunities

YW: Youth Wellness

APPENDIX 3

Provincial and Territorial Action Plans

The following scan outlines current provincial and territorial government mental health action plans for the general population. The documents were reviewed for measurable action items, goals, and plans that align with developing and maintaining high levels of population mental wellness. Common themes were identified, including:

- Action items, goals, and plans that were related to the following were not included: access, availability, transition, or wait times of mental health condition and addiction services;

- Cultural appropriateness of treatment and recovery programs for mental health conditions and addictions;

- Suicide prevention and support programs; and

- Support services for families supporting a loved one with a mental health condition or addiction.

| P/T | Name | Organization | Year | Progress | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | Valuing Mental Health: Next Steps | Alberta Government, Alberta Health | 2017 |

2019 |

HCC, RE, SW |

| BC | Healthy Minds, Healthy People: A Ten-Year Plan to Address Mental Health and Substance Use in British Columbia | Government of British Columbia | 2010 |

2012 |

FH, HCC, HW, SMH, SW |

| BC | B.C.'s Mental Health and Substance Use Strategy 2017-2020 | Government of British Columbia | 2017 |

|

FMH, HW, PP, SW |

| BC | Mental Health and Addictions: 2018/19-2020/21 Service Plan | Government of British Columbia, Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions | 2018 | 2019 | IW, SW |

| BC | A Pathway to Hope: A Roadmap for Making Mental Health and Addictions Care Better for People in British Columbia | Government of British Columbia | 2019 | FW, HW, IW, PP, SW | |

| SK | Working Together for Change: A 10 Year Mental Health and Addictions Action Plan for Saskatchewan | Government of Saskatchewan | 2014 |

2017-2019 |

FH, SW |

| MB | Improving Access and Coordination of Mental Health and Addiction Services: A Provincial Strategy for all Manitobans | Government of Manitoba | 2018 | HCC, HW, IW, SW | |

| ON | Open Minds, Healthy Minds: Ontario's Comprehensive Mental Health and Addictions Strategy | Government of Ontario | 2011 | FH, MWC | |

| ON | Better Mental Health Means Better Health | Government of Ontario | 2015 | HP, IW | |

| ON | Moving Forward: Better Mental Health Means Better Health | Government of Ontario | 2016 | ECS, FH, HCC, SW | |

| ON | Realizing the Vision: Better Mental Health Means Better Health | Government of Ontario | 2017 | ECS, HCC, CPF | |

| ON | Mental Health Promotion Guideline | Government of Ontario | 2018 | MWC, CPF, ECS, FH, SW, SMH | |

| QC* | Working together and differently: 2015-2020 Mental Health Action Plan | Government of Québec, Department of Health and Social Services | 2015 | SW, HW | |

| NB | The Action Plan for Mental Health in New Brunswick 2011-18 | Government of New Brunswick | 2011 |

2015 |

MWC, CPF, HCC, SMH, SW, TSM |

| NS | Together We Can: The Plan to Improve Mental Health and Addictions Care for Nova Scotians | Government of Nova Scotia | 2012 |

2016 |

MWC, CPF, HW, SW |

| NL | The Way Forward - Towards Recovery: The Mental Health and Addictions Action Plan for Newfoundland and Labrador | Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Health and Community Services | 2017 |

2017 |

CPF, HIAP, HP, IW, SW, TSM |

| PEI | Moving Forward Together: Prince Edward Island's Mental Health and Addictions Strategy 2016-2026 | Government of Prince Edward Island | 2016 | HW, SW | |

| NWT | Mind and Spirit: Promoting Mental Health and Addictions Recovery in the Northwest Territories - Mental Wellness and Addictions Recovery Action Plan | Government of Northwest Territories, Department of Health and Social Services | 2017 | WTD | |

| NWT | Child and Youth Mental Wellness Action Plan 2017-2021 | Government of Northwest Territories, Department of Health and Social Services | 2017 | CPF, MWC, ECS, SW, TSM | |

| YT | Forward Together: Yukon Mental Wellness Strategy 2016-2026 | Yukon Government, Department of Health and Social Services | 2016 | 2016-2019 | IW, SW |

| NT | 2010 Suicide Prevention Strategy | Government of Nunavut | 2010 | MWC, CPF, IW, FH |

* Plan to develop

CPF: Community Program Funding & Support

ECS: Early Childhood Programs & Services

FH: Family Health & Wellness HCC: Hubs/Community Centres

HIAP: Health-in-All-Policy

HP: Housing Plan

HW: Healthy Workplaces

IW: Indigenous Wellness

MWC: Mental Wellness Curriculum

PP: Parenting Programs

RE: Research & Education

SMH: Senior Mental Health & Wellness

SW: Student Mental Wellness Programs & Supports

TSM: Technology & Social Marketing Campaigns

WTD: Wellness Tracking Tool Development

REFERENCES

- PHAC, 2014. Mental Health Promotion. Promoting Mental Health Means Promoting the Best of Ourselves.

- MHCC, 2018. Measuring Progress: Resources for Developing a Mental Health and Addiction Performance Measurement Framework for Canada. Health Canada.

- World Health Organization, 1948. Constitution.

- Epp, J., 1988. Mental Health for Canadians: Striking a Balance. Can J Pub Health 79(5), 327-349.

- Kirby, J.L. and Keon, W.J., 2006. Out of the Shadows at Last. Highlights and Recommendations. Final Report of the Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. May 2006. Chapter 15. Mental Health Promotion and Illness Prevention. Ottawa.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2002. Changing directions, changing lives: the mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary, AB: Author.

- Government of Canada, 2017. A Common Statement of Principles of Shared Health Priorities.

- World Health Organization, 2018. Mental Health: Strengthening our Response.

- Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015. Definition of mental health.

- Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019. Mental Illness.

- Westerhof, G.J. and Keyes, C.L.M., 2010. Mental Illness and Mental Health: the Two Continua Model Across the Lifespan. J Adult Dev 17, 110-119.

- Keyes, C.L.M., 2002. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav 43 (2), 207-222.

- Keyes, C.L.M., 2010. The next steps in the promotion and protection of positive mental health. Can J Nurs R 42(3), 17-28.

- Keyes, C.L.M., Dhingra, S.S., Simoes, E.J., 2010. Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk on mental illness. Am J Public Health 100(12), 2366-2371.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2020. What is recovery? Health Canada, Ottawa.

- Allen, J., Balfour, R., Bell, R., Marmot, M., 2014. Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry 26 (4), 392-407.

- National Collaborating Centres for Public Health, 2017. Environmental Influences on population mental health promotion for children and youth. National Collaborating Centres for Environmental Health and for Determinants of Health.

- Mental Health Foundation, 2016. Relationships in the 21st century: the forgotten foundation of mental health and wellbeing (p. 45). Mental Health Foundation.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020. Mental Health and Mental Disorders.

- Reupert, A., 2017. A socio-ecological framework for mental health and well-being (editorial). Adv Mental Health 15(2):105-107.

- Kemp, G.N., Langer, D.A., and Thompson, M.C., 2016. Childhood mental health: an ecological analysis of the effects of neighbourhood characteristics. J Community Psychol 44(8): 962-979.

- CDC, 2020. The Social Ecological Model: A framework for prevention.

- Cramer, R.J. and Kapusta, N.D., 2017. A socio-ecological framework of theory, assessment and prevention of suicide. Front Psychol 8, 1756.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2015. Informing the Future: Mental Health Indicators for Canada. Ottawa.

- PHAC, 2017. Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework: Quick stats, Youth (12 to 17 years of age), Canada, 2017 Edition.

- PHAC, 2016. Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework. Quick stats, adults (18 years of age and older), Canada, 2016 Edition.

- Statistics Canada, 2019. Health Characteristics, Annual Estimates.

- PHAC, 2016. Canadian Best Practices Portal, Mental Health and Wellness.

- PHAC, 2018. Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait.

- FNIGC, 2018. National Report of the First Nations Regional Health Survey PHASE 3: Volume 2. First Nations Information Governance Centre, Ottawa.

- Government of Canada, 2019. Suicide in Canada.

- Statistics Canada, 2020. Suicide in Canada: key statistics.

- Gaetz, S., Dej, E., Richter, T. and Redman, M., 2016. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2016. COH Research Paper #12. Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press, Toronto.

- Agic, B., McKenzie, K., Tuck, A. and Antwi, M., 2016. Supporting the Mental Health of Refugees to Canada. Mental Health Commission of Canada.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada 2012. Why investing in mental health will contribute to Canada’s economic prosperity and to the sustainability of the health care system.

- Roberts, G. and Grimes, K., 2011. Return on Investment: Mental Health Promotion and Mental Illness Prevention. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Ottawa.

- CAMH, 2020. Mental Illness and addiction: Facts and statistics.

- Smetanin, P., et al., 2011. The life and economic impact of major mental illnesses in Canada: 2011-2041. Prepared for the Mental Health Commission of Canada. Toronto: RiskAnalytica. Cited by MHCC.

- Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2016. Making the case for investing in mental health in Canada.

- The Conference Board of Canada, 2016. Healthy Brains at Work. Estimating the Impact of Workplace Mental Health Benefits and Programs. The Conference Board of Canada, Ottawa. 54 pp.

- Canadian Coalition for Public Health in the 21st Century, 2013. Public Health: A Return on Investment. CCPH21, Ottawa.

- Roberts, G. and Grimes, K., 2011. Return on Investment: Mental Health Promotion and Mental Illness Prevention. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Ottawa.

- European Union, 2014. Joint Action on Mental Health and Well-being. Mental Health in All Policies. Situational Analysis and Recommendations for Action. European Union. 104 p.

- Waddell, C., McEwan, K., Shepherd, C., Offord, D.R., and Hua, J.M., 2005. A public health strategy to improve the mental health of Canadian children. Can J Psychiatry 50(4):226-33.

- College of Family Physicians of Canada, 2018. BEST ADVICE Recovery-Oriented Mental Health and Addiction Care in the Patient’s Medical Home. College of Family Physicians of Canada, October 2018.

- CMHA, 2018. Mental Health in the Balance: Ending the Health Care Disparity in Canada. Canadian Mental Health Association (national). 24 p.

- CPHA, 2017. Public Health: A conceptual framework. Canadian Public Health Association. Ottawa, 14 p.

- Mantoura, P., 2017. Population mental health in Canada: Summary of emerging needs and orientations to support the public health workforce. Briefing Note. National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy.

- Institute of Health Equity, 2014. Social Gradient.

- Public Health Agency of Canada and Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, 2018. Key Health Inequities in Canada: A national portrait. Executive Summary. Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa. 11 p.

- CPHA, 2016. Early Childhood Education and Care. Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa.

- CPHA, 2018. Racism and Public Health. Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa.

- CPHA, 2019. Children’s Unstructured Play. Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa.

- CPHA, 2017. Jordan’s Principle and Public Health. Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa.

- CCPH21, 2017. Core Housing Need. Canadian Coalition for Public Health in the 21st Century, Ottawa.

- CCPH21, 2017. Basic Income. Canadian Coalition for Public Health in the 21st Century, Ottawa.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.

- Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, 2015. First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework.

- Alianait Inuit-specific Mental Wellness Task Group, 2007. Alianait Inuit Mental Wellness Action Plan.

- Allen, J., Balfour, R., Bell, R., and Marmot, M., 2014. Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry 26(4), 392-407.

- World Health Organization and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2014. Social determinants of mental health. World Health Organization, Geneva. 54 p.

- Nozal, A.L., Martin, N., and Murtin, F., 2019. The Economy of Well-being: Creating Opportunities for People’s Well-being and Economic Growth. OECD Statistics Working Papers 2019/02.

- Eriksson, M., Ghazinour, M., and Hammarstrom, A., 2018. Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: what is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Social Theory and Health 16, 414-433.

- Stokols, D., 1992. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist 47(1), 6-22.

- National Scientific Council on the Development of the Child, 2010. Early experiences can alter gene expression and affect long-term development. Working Paper No. 10. Harvard University, Boston.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2019. Fostering Healthy Mental, Emotional and Behavioral Development in Children and Youth: A National Agenda. Washington, D.C.

- CPHA, 2015. Global Change and Public Health: Addressing the Ecological Determinants of Health. Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa.

- CPHA, 2019. Climate Change and Human Health. Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa.

- Cunsolo, A., 2018. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Climate Change 8, 275-281.

- CMHA, 2019. Eco-anxiety: Despair is rising. Canadian Mental Health Association, Toronto.

- Aalhus, M., Oke, B., Fumerton, R., 2081. The social determinants of health impacts of resource extraction and development in rural and northern communities: A summary of impacts and promising practices for assessment and monitoring. Northern Health and the Provincial Health Services Authority.

- CMHA, 2019. Stronger Together: Impact Report 2019. Canadian Mental Health Association, Toronto.

- Ibrahim, D., 2016. Canadians’ Experiences with Emergencies and Disasters 2014. Statistics Canada.

- United Nations, 2020. Policy Brief: The impact of COVID-19 on Women. 9 April 2020. 21 p.

- United Nations, 2020. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Children. 15 April 2020. 17 p.

- Grych, J., Hamby, S., and Banyard, V., 2015. The resilience portfolio model: understanding healthy adaptation in victims of violence. Psychology of Violence 5(4), 343-354.

- Lerch, D., 2015. Six Foundations for Building Community Resilience. Post Carbon Institute, Santa Rosa, CA. 46 p.

- Tousignant, M. and Sioui, N., 2009. Resilience and Aboriginal Communities in Crisis: Theory and Interventions. J Aboriginal Health 5 (1), 43-61.

- CPHA, 2019. Public Health in the Context of Health System Renewal in Canada. Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa.

- Mantoura, P., 2017. Population mental health in Canada: an overview of the context, stakeholders and initiatives to support action in public health. INSPQ and NCCHPP, Montreal.

- Orpana, H., Vachon, J., Dykxhoorn, J., McRae, l., and Jayaraman, G., 2016. Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: the development of the positive mental health surveillance indicator framework. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, policy and practice 36 (1).

- NCCHPP, 2017. Provincial and territorial strategies in mental health. INSPQ and NCCHPP, Montreal.

- NCCHPP, 2017. Indigenous specific mental health and/or wellness strategies. INSPQ and NCCHPP, Montreal.

- NCCHPP, 2017. Strategies related to suicide prevention. INSPQ and NCCHPP, Montreal.

- WHO, 2004. Promoting Mental Health Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- CMHA, 2019. Cohesive, Collaborative, Collective: Advancing mental health promotion in Canada. Summary Report and Full Report. Canadian Mental Health Association, Toronto.

- MHLTC, 2018. Mental Health Promotion Guideline, 2018. Population and Public Health Division, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. 25p.