Promoting Healthy Built Environments on Vancouver Island

THE PROJECT

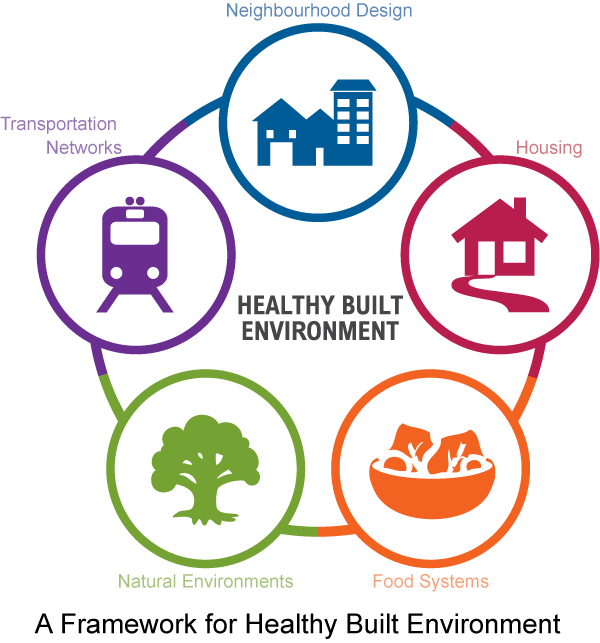

In 2013, Island Health established the Healthy Built Environment (HBE) Portfolio with the understanding of the many ways in which the design and development of communities can impact public health and health equity.

“From the outset, we had very broad goals for this portfolio. We wanted to improve health and health equity by working to ensure that neighbourhood design, transportation networks, housing, food systems, and natural environments protect health and support healthy living,” offered Jade Yehia who was the Healthy Built Environment Consultant for Island Health from 2013 to late in 2021. “We focused on different issues in different communities; on active transportation and access to healthy foods in some; on air pollution, climate resiliency, and social well-being in others.”

BACKGROUND

Vancouver Island Health Authority (Island Health) is one of five regional health authorities in British Columbia (BC), that operate with the Provincial Health Services Authority and BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) and alongside the First Nations Healthy Authority. Island Health has responsibility for community health on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands in BC. While the regional health authorities are directed, funded and supported by the BC Ministry of Health, they each have operational responsibility for their region and work closely with local communities to carry out those responsibilities.

Vancouver Island, which is about the same size as Belgium or Taiwan, is home to about 900,000 people. Surrounded by the Pacific Ocean on the west coast and the Strait of Georgia and the Queen Charlotte Strait on the east coast, it has a rugged geography with many coastal towns, a large number of First Nations communities, and several cities including Victoria, Nanaimo and Campbell River.

THE PROCESS

There are several layers to the HBE Portfolio. There are staff working in the provincial agencies who are preparing policy positions and resources to support the regional health authorities. Within Island Health, there are 1.5 FTEs who are focused on building capacity on healthy built environments across the regional health authority who also offer support to staff who are working in the field. The field staff, who are working with local communities in HBE, are Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) who have been trained as public health inspectors.

“My job as HBE Consultant was to develop internal capacity within the region and to provide technical and strategic support to EHOs in the field,” explained Yehia. “We have encouraged EHOs to work through existing community networks or other tables in their communities so they can engage directly with people in their communities.”

The community health networks that have been developed over time have been initiated by Island Health or started by community champions focused on addressing the social or environmental determinants of health. These networks include elected leaders, First Nations representatives, community groups, staff from local municipalities, and citizens.

Island Health has developed a comprehensive HBE training program for staff that includes workshops, webinars, and educational resources such as the provincial Healthy Built Environment Linkages Toolkit that was developed with the BCCDC. This training program and the resources have been well received by Island Health staff and by public health professionals in other provinces. Island Health also provides information on healthy built environments to the public through its website.

OUTCOMES ACHIEVED

“At the beginning of the program, we offered formal written comments on Official Community Plans (OCPs) as they came up for review using health evidence,” said Yehia. “But our role has evolved over time. Now we are involved in the review of master plans for parks, urban forest strategies, and the implementation of airshed roundtables and climate action plans. We are now seen as a trusted voice and collaborative partner by many of our communities.”

Given the broad goals and the long period of time that is needed to manifest the health benefits associated with healthy built environmental policies, Island Health has developed a number of process-oriented indicators to measure the success of their program. For example, they track:

- The number of land use referrals from communities;

- The nature of the land use referrals. Island Health used to be asked to review Official Community Plans only, now they are being asked to participate in the development of Active Transportation Plans, Poverty Reduction Strategies, and Parks and Open Space Master Plans; and

- The number of OCP formal tables – such as an OCP Advisory Committee to support the development of a plan’s policy statements or after the OCP has been approved the implementation of said policies (or even input on indicators being used to track progress on the OCP) – that staff are invited to, or participate in has grown over the years.

“As local partners have gotten to know us, understand our interests, and appreciate the health expertise we bring to the table, they are asking us to get involved earlier in the process and often bringing us in as partners,” offered Yehia.

The HBE program has also given rise to some significant collective impacts that were not originally anticipated. For example, in Cowichan Valley, where air pollution can become problematic during weather inversions due to the use of wood-burning stoves and open burning, the HBE team participated in a roundtable process with local governments, First Nations, industry, and non-government organizations to develop a regional air strategy. The strategy includes everything from public education to an incentive program that aims to shift home-owners from wood stoves to heat pumps. The Cowichan Region Community Health Network now facilitates the multi-stakeholder roundtable to implement the strategy.

“This roundtable has been very successful at addressing the air pollution issue in the Cowichan Valley and really demonstrates the power that collective impact can have on an issue,” said Yehia. “Much of this work came about as a result of community champions, a keen desire to address the issue of air pollution in the Cowichan Valley, and a shared leadership/governance structure built on the collective impact model.”

LESSONS LEARNED

The seven Medical Health Officers at Island Health are strong champions of the HBE program. They helped to ensure that health promotion and engagement are rooted in evidence and provided support to staff at a local level, which has increased the chances of health priorities being captured in local plans.

Staff have discovered that they are much more likely to have health priorities and language captured in OCPs and master plans when they participate directly in committee meetings.

Island Health has also learned that staff can be most effective when they focus their time and energy on issues that align with the priorities of the community or the stumbling blocks for local planners.

“For example, in Township of Esquimalt, a small community just outside the City of Victoria, the community was growing very quickly and feeling a lot of development pressure. When the OCP came up for review, the community really wanted to build language into the plan to address social well-being and social cohesion. We were able to provide them with the health rationale to support those goals. We also helped to develop a Social Well-being Survey to canvass the community on ‘Designing Density’ into multi-family dwellings. The community’s goal is to develop a social well-being checklist that can be applied to multi-family development reviews.”

Staff have also learned that “context is everything”; the issues of concern to a small, coastal community are very different than those for a large urban centre such as Victoria.

Prepared by Kim Perrotta, MHSc, Executive Director, CHASE

Last modified: October 19, 2022