Public Health and Planning Co-creating 15-minute Neighbourhoods in Ottawa

THE PROJECT

Ottawa is one of the first communities in Canada to enshrine 15-minute neighbourhoods into its Official Plan (OP).

BACKGROUND

Located on the eastern boundary of Ontario, Ottawa is the capital of Canada and has over 1 million residents. It is the fourth largest city in the country and the second largest in Ontario. Residents born outside of the country make up almost 18% of Ottawa’s population with people arriving from around the world.

Ottawa’s economy is built largely around the technology sector and the federal government, but also benefits from a vital rural sector that contributes over $1 billion to the GDP. Ottawa’s agricultural sector includes about 300,000 acres of farmland and 1,300 agricultural operations and employs approximately 10,000 people.

Ottawa Public Health (OPH), which has responsibility for community health in Ottawa, is part of the City of Ottawa with a semi-autonomous Board of Health.

THE PROCESS

OPH co-located two of its staff in Ottawa’s Planning, Real Estate and Economic Development department for three years with the goal of having the City’s new OP rooted in a framework that creates healthy, inclusive and resilient communities.

“We were using what we characterized as the ‘Five C’s – compact, connected, convivial, complete and cool’ to describe our vision of the neighbourhoods that we wanted to create, but we found it difficult to advance this vision to the public and to our colleagues in planning in a way that integrated all of these features through planning levers,” explained Inge Roosendaal, Senior Planner with OPH. “We wanted a cohesive framework that would capture the concept of the five Cs so we pitched the idea of the ‘15-minute neighbourhood’ and it resonated with our stakeholders and communities.”

One of the OPH staff was a registered professional planner with a master’s degree in planning and experience in public health who understood the land use planning process and population health. The other had a master’s degree in geography with a specialization in environmental sciences, and work experience in health hazards, environmental policy, climate change, and urban planning.

“It was seminal to the achievement of public health’s goals that we were assigned to work with the Planning Department for the entire OP process,” noted Inge. “In the past, we were consulted only. This time, we were fully engaged at every stage in the process.”

“This allowed us time to gather relevant health evidence and to prepare one of the background papers that informed the development of the OP,” said Inge. “But more importantly, it gave us time to engage in discussions with colleagues in other departments and participate in meetings with consultants, the public, and developers at every stage in the process.”

The two public health staff had the support of senior staff in public health, including the Medical Officer of Health (MOH), as well as the support of the General Manager (GM) for the Planning, Real Estate and Economic Development department. The GM expressed the view that his goal was to have a new OP that ambitiously supports positive health outcomes as well.

“We consulted with other staff in public health, including senior staff, but ultimately, we were the people in the room, dealing with a wide range of complex and interconnected issues,” noted Inge. “Our senior staff understood that the process could not work if we were not empowered to make decisions with staff from other departments.”

The concept of the 15-minute neighbourhood was captured in a high-level policy directions report called the “5 Big Moves” that was approved by Ottawa City Council in September 2019 and became the framework around which the OP was built.

“We were consulting with the public on the 15-minute neighbourhood concept during the pandemic, so residents were really feeling the impact that their neighbourhoods were having on their daily lives,” said Inge. “That helped people appreciate how neighbourhood design affects their physical and mental well-being by influencing whether they can walk and cycle safely, access essential services, connect with others outdoors, get relief from extreme heat, or enjoy parks and greenspace.”

THE OUTCOMES

The new OP, which was approved by Ottawa City Council in November 2021, will guide development in the City until 2046. The City’s vision – to become the most livable mid-sized city in North America over the next century – is supported by five broad policies:

- Accommodate more growth with intensification of existing neighbourhoods rather than with greenfield development.

- Ensure that the majority of trips in 2046 will be made by sustainable modes of transportation such as walking, cycling, transit or carpooling.

- Use sophisticated urban and community design principles to create stronger, more inclusive and vibrant neighbourhoods and villages that also reflect and integrate Ottawa’s economic, racial and gender diversity.

- Embed environmental, climate and health resiliency and energy into the framework of planning policies to support walkable 15-minute neighbourhoods with a diverse mix of land uses, mature trees, greenspaces, and pathways, that help the City achieve its net zero climate commitment for 2050 and its 40% urban forest canopy cover target, and increase the City’s resiliency to the effects of climate change.

- Embed economic development into the framework of the planning policies.

- The OP includes six cross-cutting strategic policy directions that will be advanced with implementation policies that are captured in multiple sections of the OP. Three of these policy directions are: Healthy and Inclusive Communities, Climate Change and Energy, and Gender and Racial Equity.

The OP includes specific policy ‘hooks’ for these cross-cutting policies to help ensure that the strategic goals are implemented through multiple planning aspects and levers. Because the OP sets the broad policy framework for how Ottawa grows, these policy hooks will be supported by other policies and plans that have been, or will be, developed by the City. For example, the City released a 15-Minute Neighbourhoods Baseline Report in September 2021 that analyzes existing neighbourhoods using newly developed criteria and methodology for assessing 15-minute neighbourhoods and identifies the next steps for implementing the policy goals enshrined in the OP.

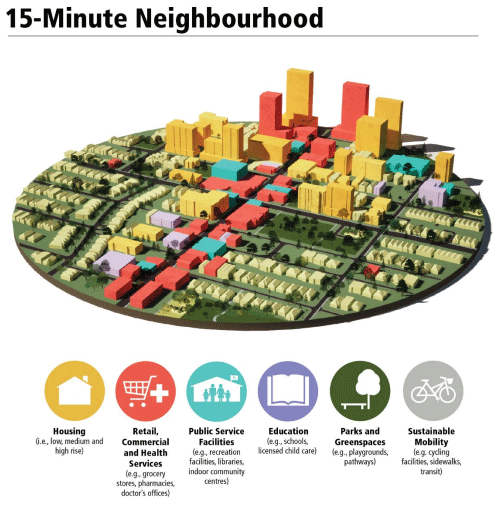

Ottawa describes 15-minute neighbourhoods as: “compact, well-connected places with a clustering of a diverse mix of land uses; this includes a range of housing types, shops, services, local access to food, schools and day care facilities, employment, greenspaces, parks, and pathways. They are complete communities that support active transportation and transit, reduce car dependency, and enable people to live car-light or car-free.”

“In the planning field, there are so many factors and tensions that need to be weighed and considered. We can’t just pass along the health evidence and walk away; we need to be in the room, to understand the other factors that need to be considered, and to inform conversations to find a way that balances health perspectives with all of the factors, needs and realities,” offered Inge.

LESSONS LEARNED

This project has provided a number of lessons for OPH:

- Public health needs to recognize the interconnections among public health, built environment, climate change, biodiversity and health equity in its approach to public policy in keeping with the World Health Organization’s Geneva Charter of Well-being. High-level policy work must be boundary-spanning, reduce silos within public health agencies and cut across programs, issues and disciplines to be efficient and effective.

- The 15-minute neighbourhood is pivotal to addressing public health, climate change and health equity at a community level.

- Public health can have a substantial impact on the social determinants of health (SDOH) such as transportation networks, the built environment, and housing if it commits the time and staff resources needed to fully engage in land use and transportation planning processes.

- It is helpful if the public health staff involved in these processes have specialized training in land use and urban planning, climate change, environmental health, and/or policy development.

- Policy windows can open and close quickly, and issues are often very complex; as such, senior staff have to be willing to empower staff to make decisions at working group and committee meetings.

- Public health would benefit from having policy staff who can work at a high level with other departments and/or jurisdictions to address the ecological determinants of health (EDOH) such as the built environment, climate change, and air quality, as well as the SDOH, that affect the health of the public.

“The 15-minute neighbourhood is the key lever for advancing climate resiliency, public health, and health equity at the community level,” noted Inge. “Many of the features needed to improve public health and health equity, such as walkable neighbourhoods rich in amenities, cycling infrastructure, efficient transit service, well-developed tree canopies for shade, and greenspace, are the features needed to reduce greenhouse gases and increase climate resiliency.”

Prepared by Kim Perrotta, MHSc, Executive Director, CHASE

Last modified: June 17, 2022